(reading time: 9 minutes)

(header image from edutopia)

So earlier this year, I learnt my whole career was based on a lie. As one does.

I make games to help folks learn by doing. People learn all kinds of complex mechanics entirely "by doing" in games like Portal, right? And it's fun! Of course beginners learn better from pure exploration, rather than being railroaded through step-by-step instructions.

Anyway, this idea's been experimentally tested, and it's replicatably false.

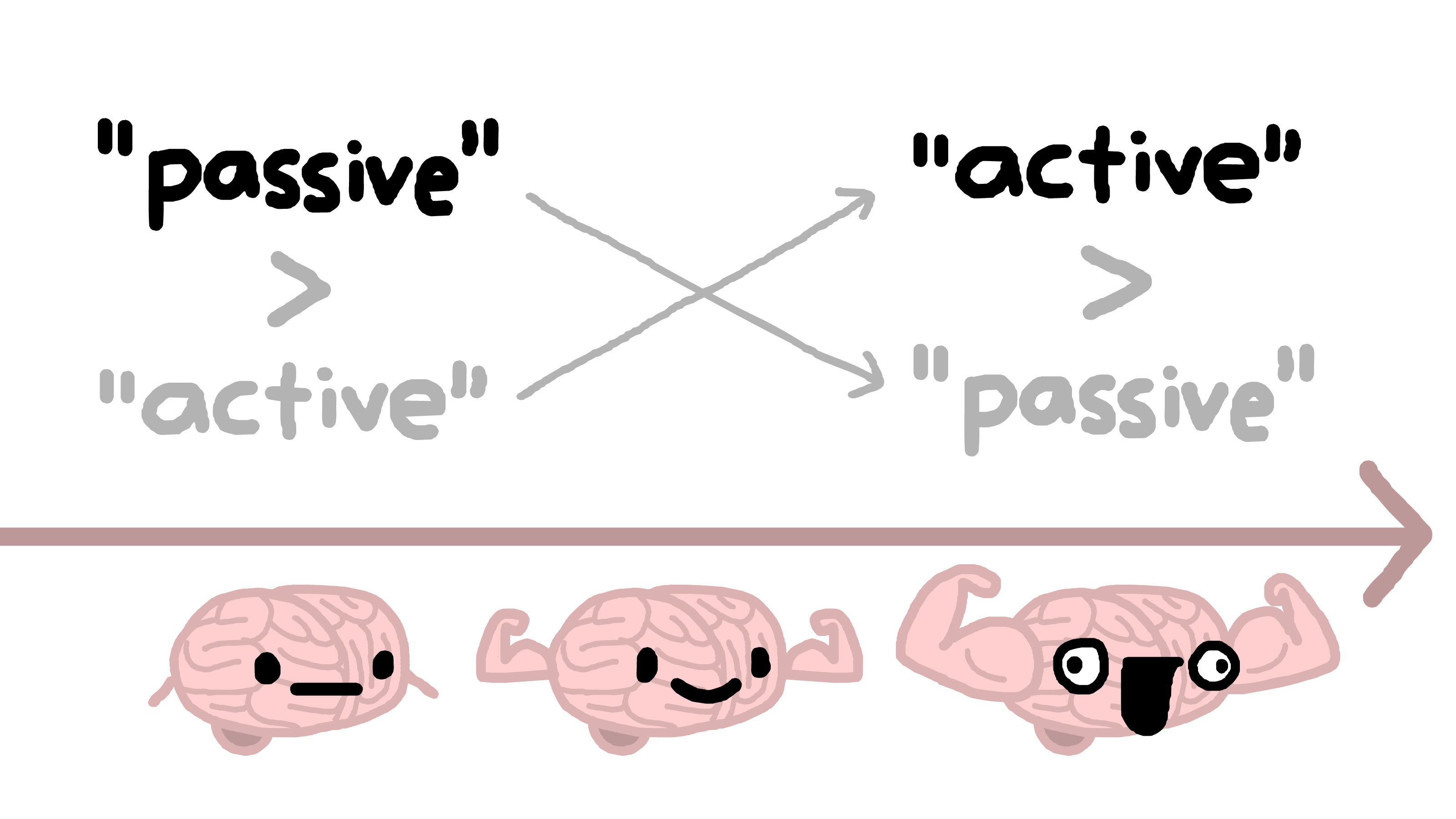

But here's where this goes from disappointing to bizarre: "active" learning-by-exploring is ineffective for beginner students, but very effective for advanced students! And "passive" learn-by-step-by-step-instruction is effective for beginners, but ineffective for the advanced.

This paradox is called The Expertise Reversal Effect.

(slide from a talk I'll post online soon!)

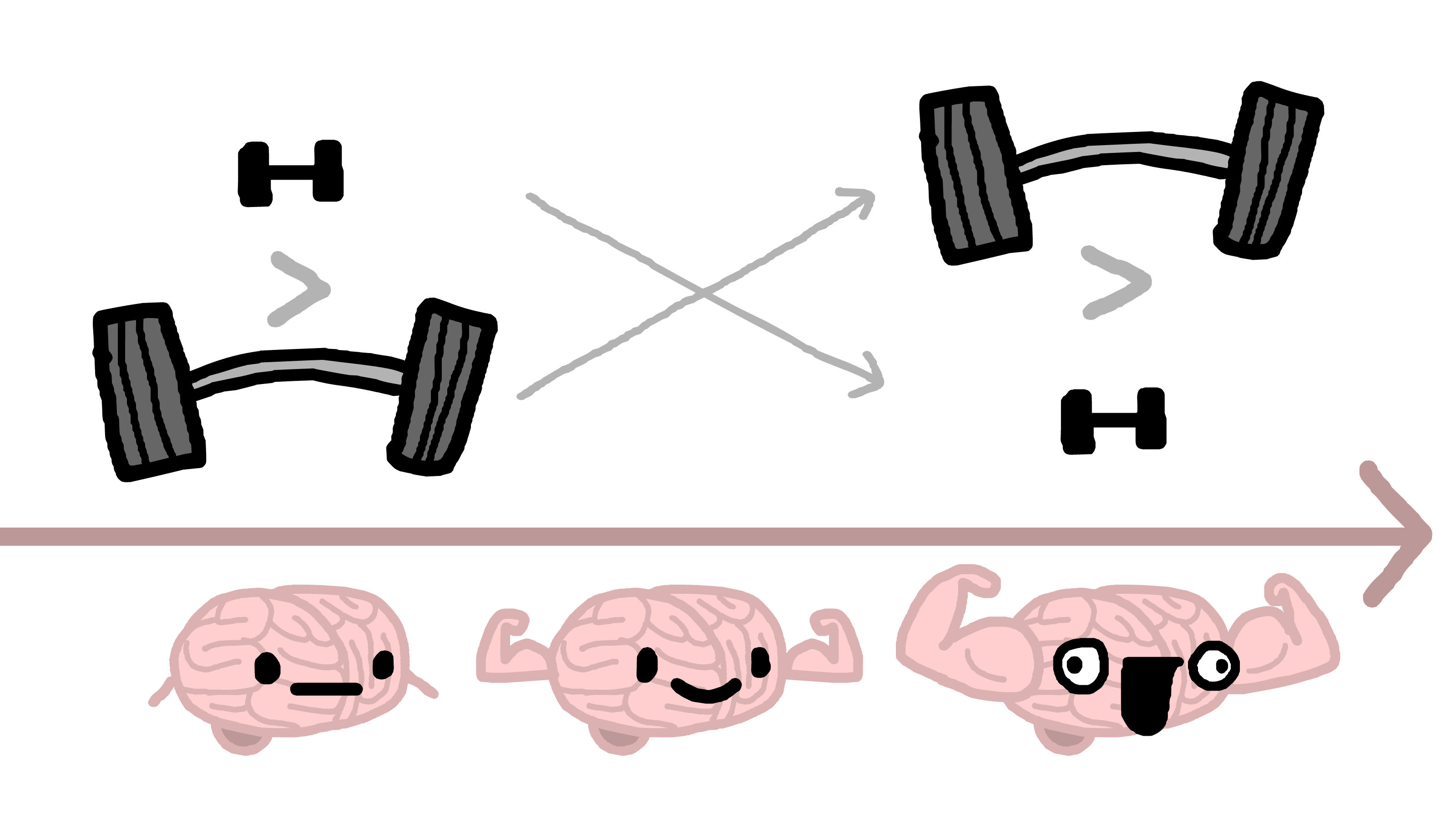

But maybe I shouldn't be surprised. Trying to bench-press 200lb would kill a beginner weightlifter, but it's good for an advanced weightlifter. Like physical load, there's cognitive load: step-by-step instructions are a "small" load, while pure exploration is a "heavy" load.

According to Cognitive Load Theory, good education is giving a learner a fitting "load": one that's slightly beyond their comfort zone. (See: Zone of Proximal Development, scaffolding)

(P.S: Here's a good reply to the original "minimally-guided learning is bad" paper, but here's an equally good reply to that reply + others)

Oh, as for "learning-by-doing" in games like Portal, it turns out the designers add tons of hand-holding guidance – they just keep it invisible so you can feel smart.

. . .

So if you're an educator or someone who "communicates through multimedia" like me, what should we do?

Richard Mayer has applied Cognitive Load Theory to create 10 empirically-based Principles for Multimedia Learning. These principles include: cut out the irrelevant "fun" fluff, organize things step-by-step, signal the important parts, etc. This doesn't mean being dry, just clear and minimalist.

But, still...

I like the fun fluff.

Leonard Susskind's The Theoretical Minimum is a technical introduction to physics by one of the world's top physicists, yet each chapter is sprinkled with silly dad jokes. Cognitive Load Theory predicts these to be "extraneous load" that would hurt learning, but I think the dad jokes are necessary.

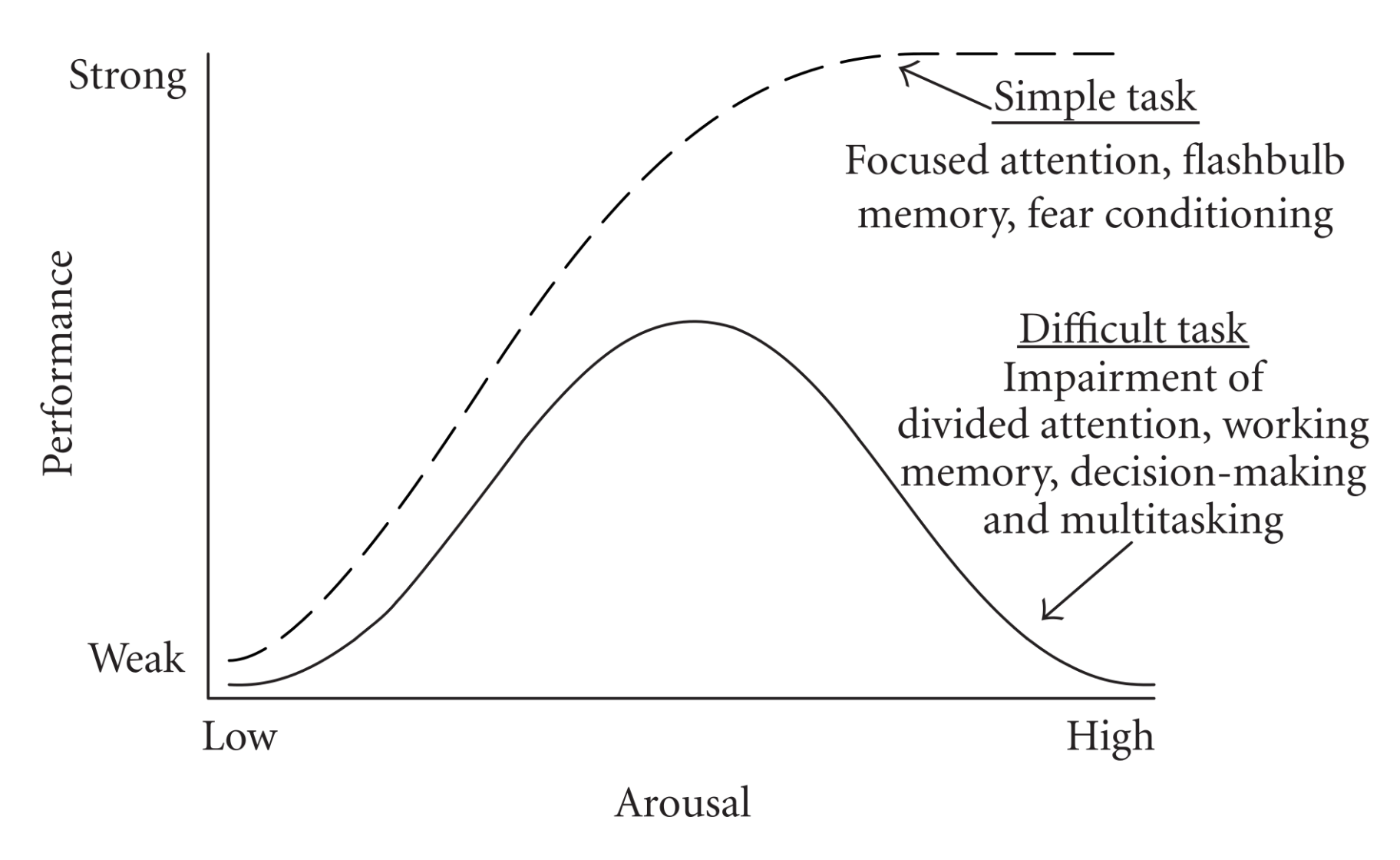

Consider Yerkes-Dodson's Law. For complex tasks – like learning a new thing – too little or too much stress leads to poor task performance, but there's a "just right" amount of stress for the best task performance:

Back to Susskind's books: tensor products are pretty stressful, so dad jokes help bring the stress level back down to the optimum. Same technique is used in other technical-but-fun (fun-but-technical?) stuff like 3Blue1Brown, Gödel Escher Bach, Mathematical Games, etc.

That's the big gap in the original version of Cognitive Load Theory: it says nothing about emotion... even though neuroscientists & psychologists have known for decades that the "cognition-emotion divide" is bull! (See: Lazarus 1991, Descartes' Error)

So last month, I found 4 helpful papers about emotion in learning!

Paper #1)

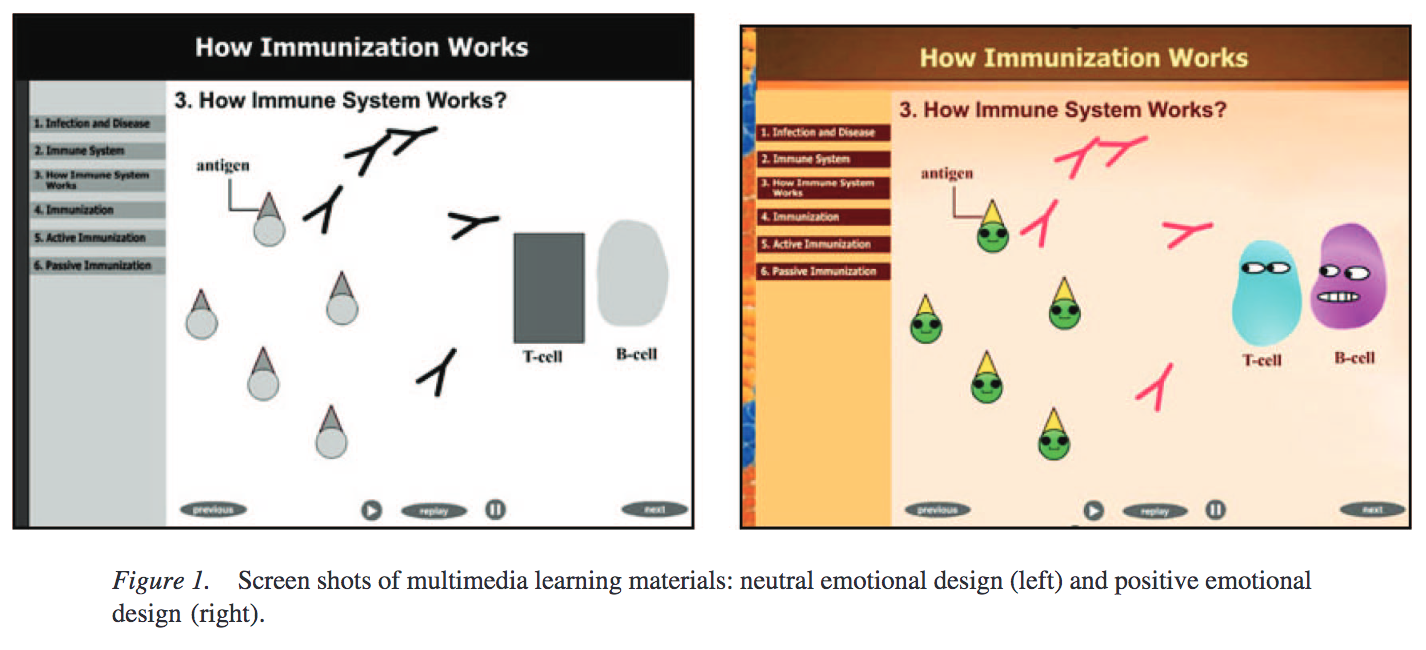

I'm very pleased Um et al 2012 provides empirical support for my approach to teaching: "slap a bunch of silly faces on it".

Obviously, making something more "fun" makes a learner more motivated to keep going. But this study found something stranger: making something more "fun" improved learning outcomes directly, not through motivation alone.

Three possibilities why:

- The Yerkes-Dodson thing I mentioned earlier.

- Memories stick better when they're emotional. (including painful memories)

- Being in a relaxed mood actually "opens your mind" more. (Imagine how close-minded people get when they're scared!)

But what about all the other research showing that interesting-but-irrelevant "seductive details" damage learning? And in the "educational games" practice, it's frowned upon to create "Chocolate-Covered Broccoli", coz kids can smell the bull from miles away.

The difference between the chocolate-covered broccoli and the Um et al paper is that the extra "fun stuff" is actually relevant. Thus, they don't misdirect attention – in fact they help focus it! The cute faces are only on the important biological agents, while the unimportant background & buttons stay relatively boring.

(Same with Susskind's The Theoretical Minimum – it's not filled with jokes, just sprinkled with them. There's only 1 pun per 10 pages, and each one is relevant to the learning material. More or less.)

But still, this technique somehow feels like... cheating? Lymphocytes aren't that cute in real life. Is there a way to get learners to feel positive emotions about the material without resorting to cute doodles?

Yes! Let's get curious, about an emotion called curiosity.

Papers #2 and #3)

Monkeys will solve puzzles for food. So far, so behaviourist.

But: Monkeys will solve puzzles even without a food reward. In fact, introducing food as a reward made the monkeys learn worse. Understanding the unknown is already a biologically fundamental reward in itself.

Same for us monkeys. Contrary to the "logical thinking means being dispassionate" myth, the world's top mathematicians and scientists are driven by a specific emotion: curiosity. (Also desperation over grant funding)

But what, then, causes curiosity?

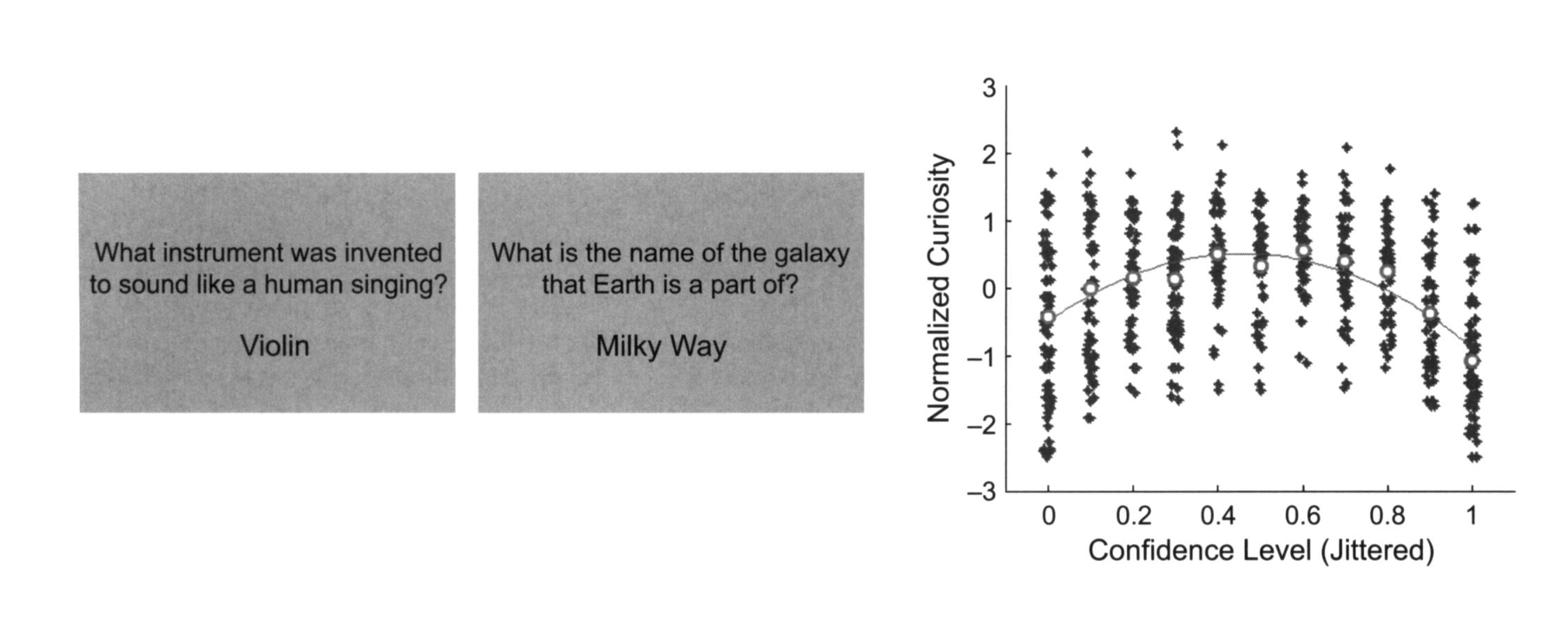

Kang et al 2009 was a neuroscience study that found three things:

- being more curious led to more activation in reward & memory neural circuits,

- being more curious led to better recall, and

- we're most curious when we have a medium-level of confidence in our answer.

Like the Yerkes-Dodson curve, it's another upside-down U shape. When the answer's obvious, well duh we're not curious – it's "too comprehensible". But when we have no idea what the answer even could be, we also don't care – it's "too complex".

But in-between, when you balance complexity and comprehensibility, then monkeys get curious!

NOTE: Cognitive Load Theory can't predict a such thing as "too comprehensible"! This leads to different implications for science communication: instead of giving the information in a logical order bridging all the gaps ("blah blah blah here's the formula for orbits"), you should first reveal a medium-sized gap in the learner's knowledge ("if gravity keeps the moon near us, why doesn't the moon fall down?"), to stimulate the learner's curiosity! Show the gap, then build the bridge.

Silvia 2008 reports the same thing. I just want to include this 🌶 spicy 🌶 paragraph of his:

College textbooks are an intriguing example. The typical textbook wants to engage students’ interest, so it sprinkles each chapter with irrelevant quotes, cartoons, contrived stock photos, and random stories from the authors’ distant childhoods. But diverting attention from the text’s main points isn’t the same thing as making the text’s main points interesting.

[...]

If interest comes from seeing something as new and comprehensible, then people who want to evoke interest should try to enhance both complexity and comprehension.

That is: don't coat the broccoli in chocolate.

Paper #4)

When I started writing this post, I intended to include just the 3 papers above. But as I hunted down my citations, I found this extra gem.

You remember above, when I said:

That's the big gap in the original version of Cognitive Load Theory: it says nothing about emotion

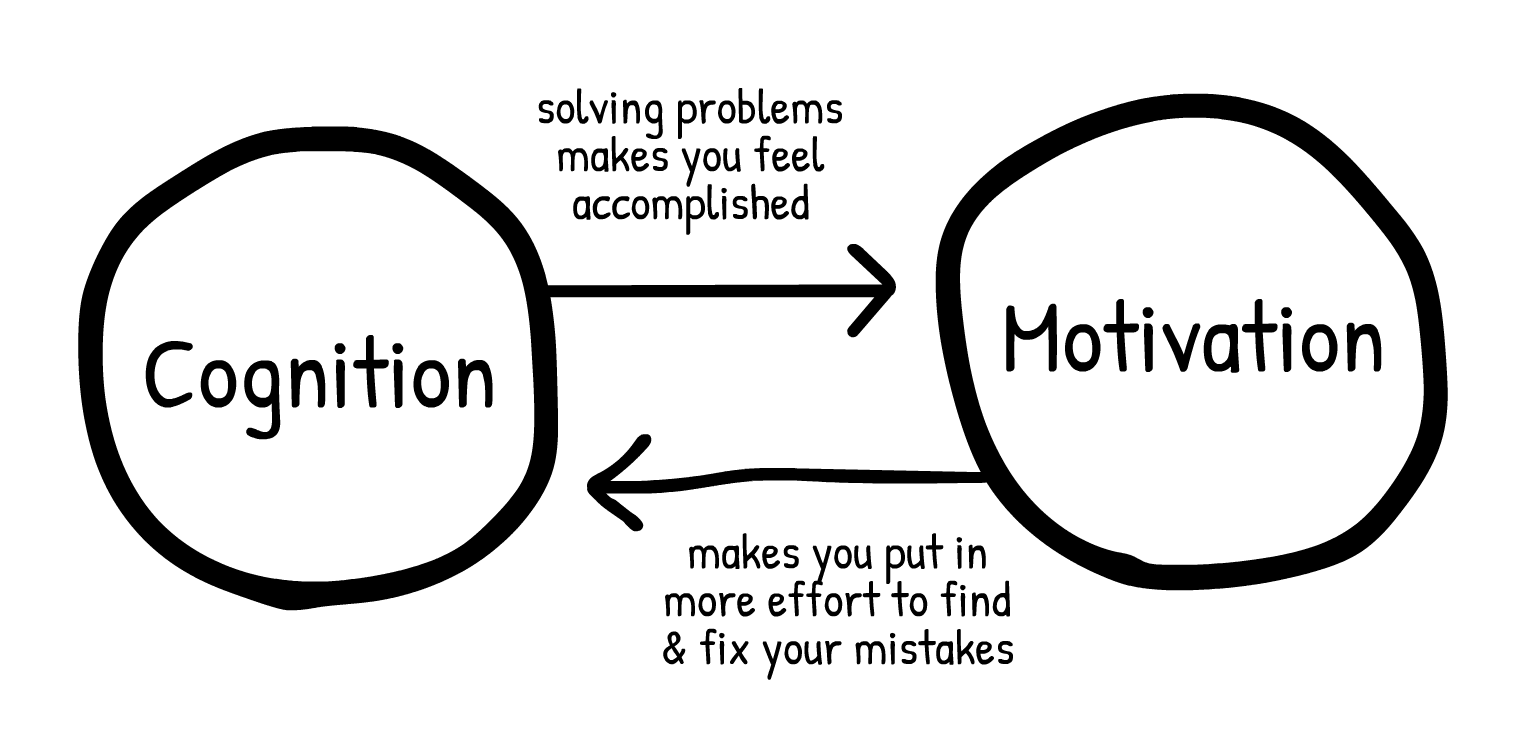

Turns out people have recently added emotion and motivation to Cognitive Load Theory. Moreno 2010 recaps the problems with the old theory, and summarizes a new theory: Cognitive-Affective Theory of Learning.

It proposes a loop: (Bad drawing by me)

You'll learn poorly if you're not motivated, and you'll be demotivated if you're learning poorly. But, from vicious to virtuous cycle: you'll learn well if you're motivated, and you'll be more motivated if you're learning well!

So, if you make "multimedia learning", the trick is to boost both sides of the loop:

(💥💥💥 THIS IS THE SUMMARY SECTION 💥💥💥)

- Improve Cognition with:

- Cognitive Load Theory – remove distractions, organize info, signal what's important, etc

- Zone of Proximal Development – keep the cognitive load difficulty just above the learner's comfort zone.

- Improve Motivation with:

- Relevant fun – add "fun" stuff only if it highlights the important parts.

- Curiosity first – show a (medium-sized) gap, then build the bridge.

(💥💥💥 / END SUMMARY SECTION 💥💥💥)

I've made lots of chocolate-coated broccoli before. A science piece with irrelevant stories, a math explainer with strained pop-culture references, a simulation with unnecessary "ooh solve the puzzle!" game-y bits.

The original Cognitive Load Theory taught me to strip the chocolate off my broccoli. But finding out that emotion directly improves learning? That taught me I need to season & roast those veggies, to bring out the natural tastiness that's already in the broccoli. As the monkeys showed us, there's a natural motivation already in understanding the unknown.

There's the junk food of bad edu-tainment, and the Nutra-Loaf of dry academic papers. The trick to sticking to a healthy diet is to cook stuff that's both delicious and nutritious.

(this essay was originally posted on my Patreon, as part of my patron-exclusive “What's Nicky Learning?” monthly series, where I share what I learn as I learn it!)