Four years ago (wow, already four?), we had the first-ever Explorable Explanations meetup, to talk about teaching through play.

We had no idea what we were doing. Still don't.

But, four years later – after 100+ Explorables made by educators, journalists, and curious laypeople like yours truly – I think we figured out a bit more on how to share complex, powerful, beautiful ideas through play. So here's a listicle about that.

Pattern #1: Puzzle It Out

(sidenote: from SineRider)

(sidenote: from SineRider)

Not all learning-by-doing is equal. In high school, I did lots of those chemistry "experiments" where the teacher just tells you exactly what to do and exactly what result to expect. I remember setting my hand on fire. I don't remember any actual chemistry, though.

That's because even though our lab was hands-on (especially hands-on-fire), and we "did" things, we didn't do the one thing needed for learning anything: thinking.

Not so in Chris Walker's SineRider! In this TI-86-inspired puzzle game, you create a wintery landscape by graphing equations, to slide your tobogganer characters to their goal. Instead of mindlessly following an algorithm to get the One True Answer™, you're forced to actually think about how equations become curves and vice versa, and invent your own solution out of ∞ possible solutions.

Chris repeated this puzzle-based design in District, and inspired me to give puzzles a shot in The Wisdom and/or Madness of Crowds. Puzzles, besides adding a tasty challenge, also make your players prove they actually understand the underlying ideas before they can move on. "Teaching" and "Assessment" get rolled up in one.

This Design Pattern is good for: teaching topics that lend themselves to simulation, e.g. math, programming, science

But if making a whole simulation is too much, there's a simpler way to challenge your players, and that's with...

Pattern #2: Place Your Bets!

(sidenote: from You Draw It)

(sidenote: from You Draw It)

Learning requires thinking. That's why simply giving someone "the answer" often fails. However, asking your reader to puzzle out the answer every time may be impractical, so you can do the next best thing: give them the answer, but only after they've wrestled with the question.

The Upshot's You Draw It series (on education, obama, overdoses) does this well. Instead of showing you a graph of some statistic upfront, the website first makes you draw what you think the graph should look like. Only then, it reveals how your expectations (mis)match with reality. By forcing you to put down your expectations, the real answer comes as a bigger shock. (for me, my holy-crap moment was seeing how much I'd underestimated the opioid epidemic)

This place-your-bets pattern also appears in The Pudding's Birthday Paradox, and in my The Evolution of Trust. In Steven Strogatz's essay, Writing about Math for the Perplexed & Traumatized (pdf), he talks about how ineffective traditional math teaching is, because “it answers questions the student hasn’t thought to ask.” The solution: “You have to help them love the questions.”

This Design Pattern is good for: teaching topics with a clear right or wrong answers

But what if what you're teaching doesn't have a clear right or wrong answer? What if it's about philosophy or politics or ethics? In that case, you could try...

Pattern #3: Role Play

(sidenote: from A Syrian Journey)

(sidenote: from A Syrian Journey)

I did it! My family and I escaped Syria, traveled to Turkey, and made it across the river in a small inflatable boat onto Greece's shore. Finally, we -- oh, القرف. A second boat just capsized behind us. A woman and her daughter are struggling in the water. Do I dive in to save them, and risk getting caught by the border guards... or do I run into the woods with my family, and leave the mother and girl to their fate – a fate which could have just as easily been ours?

That's a scene from BBC's A Syrian Journey, an interactive story based on real Syrian refugee stories. It's more than creating "empathy" – a word now on par with "synergy" and "paradigm shift" – it makes you actually think (and thus learn) about the dilemmas that refugees face.

Some other role-playing explorables include: BBC's Crossing Divides, Pippin Barr's Trolley Problem, and Gabrielle LaMarr LeMee's Educate Your Child. In all of these, there are no right answers, but they still make you think about the right questions.

This Design Pattern is good for: exploring hard questions about philosophy, politics, ethics, or life

But what if your topic not only has no right answers, but also no right questions? To maximize the "explorable" in "explorable explanation", you could look at our final design pattern...

Pattern #4: Sandbox Mode

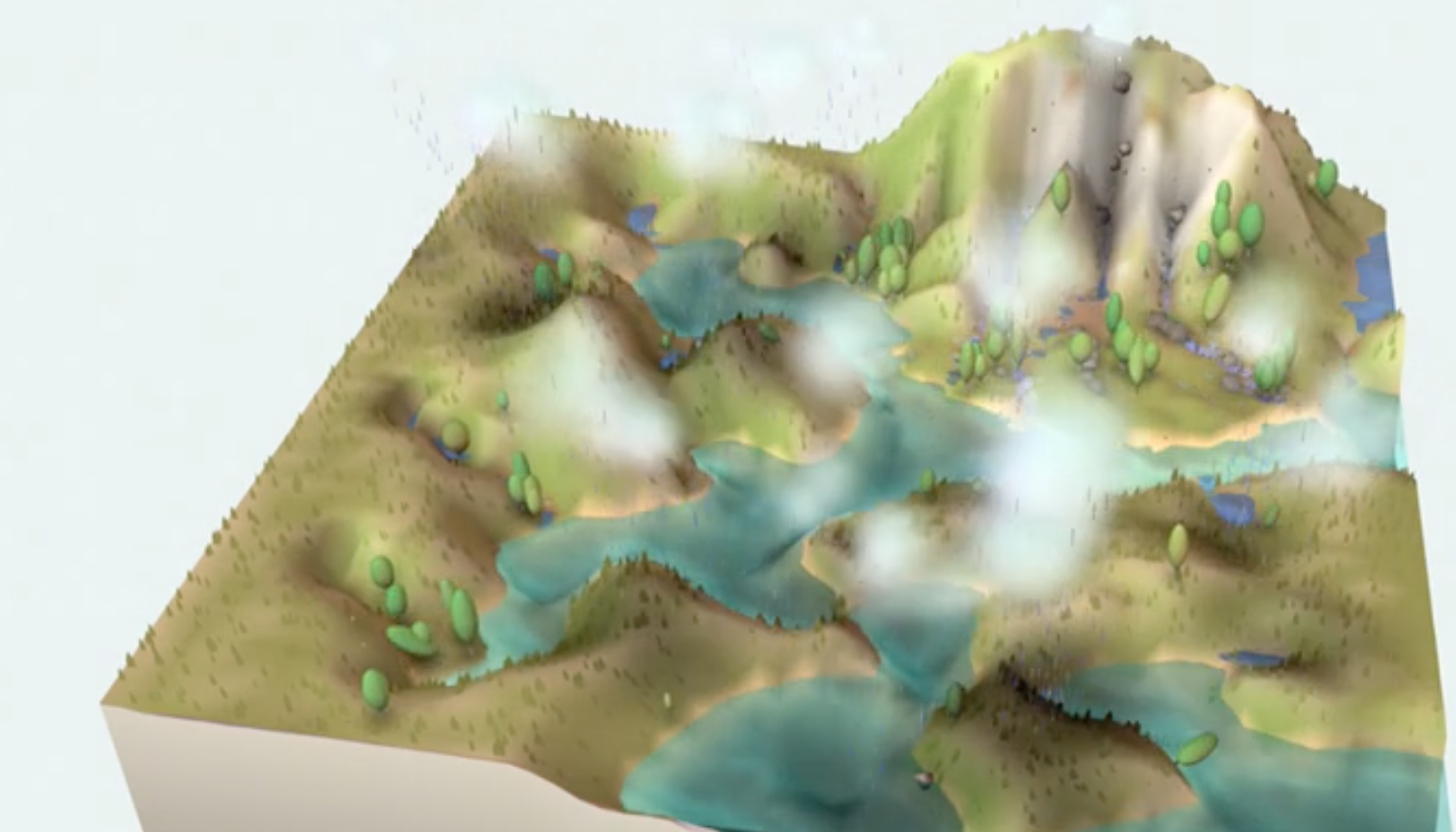

(sidenote: from Earth: A Primer)

(sidenote: from Earth: A Primer)

Just give your reader a big simulation to play around in, with little to no guidance. The upside of throwing your audience into the deepest end of the pool is that this is the way to get the deepest form of knowledge. The downside is they could drown.

Learning requires thinking. But if you give someone a task that's far beyond their current capabilities, they'll just drop it – like a dumbbell that's too heavy. For example, Daniel Smilkov & Shan Carter's A Neural Network Playground is a well-designed simulation, and my friends who already know a bit about machine learning find it useful... but for me, it's information overload. I've no idea how to even begin getting the idea.

One way to avoid this is to make a really simple simulation. Your player is thrown into the deep end of the kiddy pool. That's not to say it can't be an amazing kiddy pool! Ableton's Learning Music lets you create your own simple compositions with a digital drum machine, and Neil Thapen's Pink Trombone lets you play with a (hilariously horrifying) simulation of the human voice.

Another solution is to put the full "sandbox mode" at the end of the explorable, and everything leading up to that just introduces bits and pieces of the sandbox. This approach was taken in Chaim Gingold's Earth: A Primer, and my + Vi Hart's Parable of the Polygons. You start by dipping your toes in the shallow end of the pool, then gradually go deeper.

This Design Pattern is good for: understanding simulations in science, or using tools in art/music

· · ·

Of course, these aren't the only design patterns that have been invented, or have yet to be invented! There's so many fundamental questions:

- Can an explorable let you go beyond its author, and let you challenge the author's conclusions using the author's own simulation? (see Bret Victor's vision)

- Can an explorable augment human intelligence itself, like writing once did? (see Douglas Engelbart's vision)

- Can explorables that teach skills, not just ideas?

- Can readers learn and make things together, not just individually?

- Can an interactive be – to paraphrase this article on "the death of interactives" – like having a tête-à-tête conversation with an expert on a subject, patient enough to explain to you everything?

Nobel Laureate Carl Wieman once compared our current educational practices to ancient medical practices, and called lectures “the pedagogical equivalent of bloodletting”. I don't know what the future of learning looks like, but I – and the explorable explanations community – bet it'll be the pedagogical equivalent of kids getting exercise by racing along the beach, immersed in sunlight and fresh air, building tiny castles on the shore of a deep, vast, and beautiful ocean.